The success of ace filmmaker Pa. Ranjith and his films, lauded by critics, paved way for the liberation of Dalit characters into Tamil cinema from the past decade.

Indian cinema, born under the clutches of imperialism, had undoubtedly maintained the space or difference between the elites and the marginalised. In recent years, the audience as well as the cinema industry have made a gradual but apparent shift in the screen space for sharing the voice of the voiceless in mainstream cinema and celebrating the identity and understanding the film critically. Caste has been considered as one of the elements of oppression in the society. Caste stratification attached with religion, particularly the Varna system with Hinduism is undeniably a benchmark of the Hindu society to establish caste differentiation. When it comes to Tamil Cinema, it showcased caste either as glorification of the elites and intermediate castes or as eradication of the prevailing caste system. Many scholars in the domain of caste and cinema opine that mostly films try to eradicate caste dominance between the higher and submissive caste groups, but it is very rarely represented in mainstream Tamil Cinema.

Tamil cinema maintained a space and difference in terms of projecting the dominant and the subaltern classes through the cinematic medium. It represented the subaltern as a sidelined body, submissive and impure; whereas the dominant- intermediate caste are heroic characters with imaginary heroism – lordly, generous, fearless, gore, assertive, violent and even trouble-makers. As similar to the Gramscian thought of hegemony and counter-hegemony, the dominant caste holds the hegemony and the narratives of subaltern caste groups in Tamil Cinema holds the counter-hegemony. Many scholars in this realm of caste and Tamil Cinema have used the ‘common-sense theory’ of Antonio Gramsci to critically analyse subalternity in Tamil Cinema. Though, the word ‘subaltern’ was first used by Gramsci, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, an acclaimed scholar, literary theorist and a feminist critic affirms in her much acclaimed essay ‘can the subaltern speak?’ that “subaltern is not just a classy word for oppressed, for others, for somebody who is not getting a piece of the pie”.

The celebration of these south regions as the realm of the Thevar caste groups are very clearly shown in the Tamil films like Karimedu Karuvayan (1985), Thevar Magan (1992), Paruthiveeran (2007), and Subramaniapuram (2008).

It has been almost two years since the release of the film Pariyerum Perumal. The film is still relevant and strong, that it showcased the vile sides of caste which is deeply entrenched with the society by manifesting the socio-political and cultural elements of the south Tamil Nadu. The entire film pivoted around the Tirunelveli and Thoothukudi regions of southern Tamil Nadu, regions considered as the landscape of caste clashes and violence between the land-owned intermediate caste and the oppressed lower caste. It is very apparent in Tamil Cinema that these southern regions of Tamil Nadu are portrayed as the paramount of dominant-hegemony and intermediate caste groups who perpetrate acts of violence, victimising the lower caste marginal groups. The celebration of these south regions as the realm of the Thevar caste groups are very clearly shown in the Tamil films like Karimedu Karuvayan (1985), Thevar Magan (1992), Paruthiveeran (2007), and Subramaniapuram (2008).

Therefore, it is very evident in Tamil Nadu, where Tamilians are an effective audience of cinema. They celebrate the popular culture in their life, as it is embedded with them and they also try to manifest their culture through cinema. It is very apparent in the success of Dravidian politics and films of M G Ramachandran, J Jayalalitha, and the writings of K Karunanidhi.

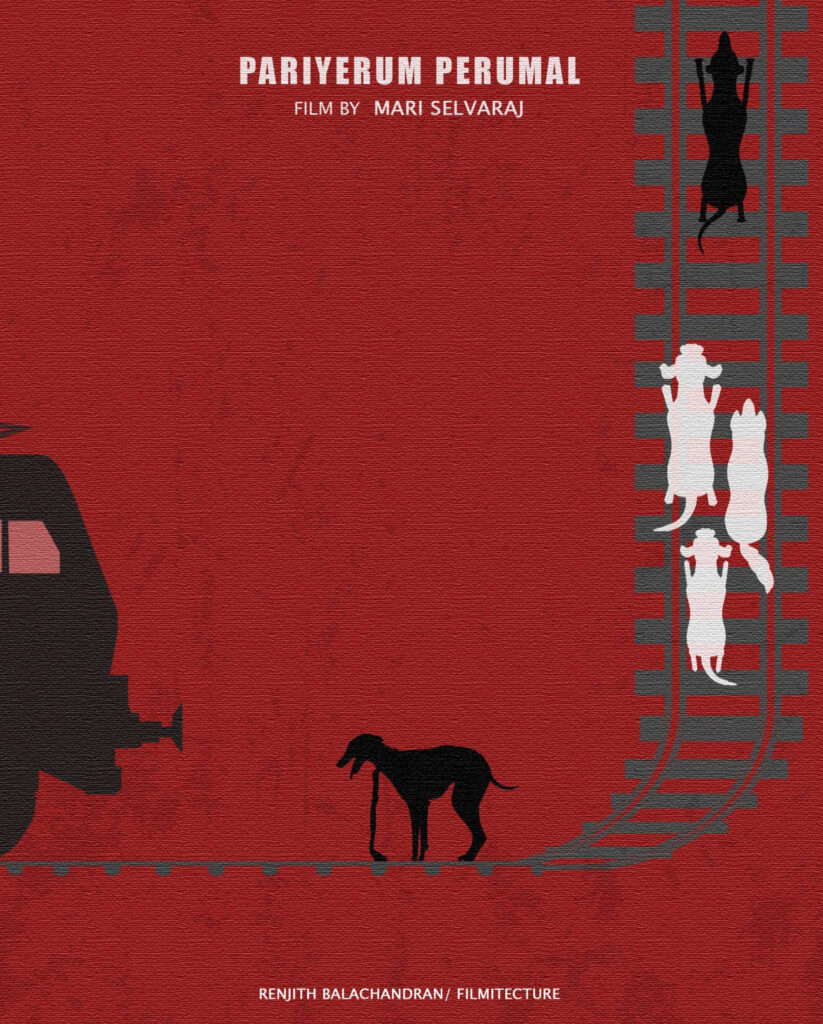

Pariyerum Perumal (tr. a folk god who mounts on steed) is a caste narrative which intensely showcased the reality and incivility existing in a caste-ridden society where the people are classified based on caste, creed and colour, clustered as the intermediate caste and the oppressed caste in South Tamil Nadu. Since it narrates a caste ideology, it never tried to explicitly represent the dominant and the oppressed caste groups. There are many other Tamil films which directly mentioned the caste name as well as acts of dominance and violence towards the oppressed communities. The success of ace filmmaker Pa. Ranjith and his films, lauded by critics, paved way for the liberation of Dalit characters into Tamil cinema from the past decade. It made an unparalleled revamp in Kollywood film industry by representing the life of the oppressed in the silver screen and connecting the Ambedkar-Phule ideologies by demolishing the stereotypical portrayal in Tamil Cinema from the past three decades.

The film has represented the extremity of dominant-intermediate and subaltern caste through various symbolic and metaphoric elements using visuals, songs, lyrics, bodily codes, caste icons, and symbols, etc.

Pariyerum Perumal can be defined as an artistic masterpiece of representing the subaltern voice as well as showcasing the odious side of the caste system prevailing in South Tamil Nadu. The songs and the subtle (metaphoric and symbolic) representation of caste reality makes the film all the more poetic and a treat for the eye. The film has represented the extremity of dominant-intermediate and subaltern caste through various symbolic and metaphoric elements using visuals, songs, lyrics, bodily codes, caste icons, and symbols, etc. The submissive caste groups are represented and can be identified through worship differentiation (Folk-god worship), village name and language slang, practice of double-tumbler system, mentioned as landless labourers under landlords and hegemonic caste groups, assertive dialogues with rhetoric connections to Viduthalai Chiruthaikal Katchi (VCK) (Dalit Panthers Movement) a dedicated Dalit Political party in Tamil Nadu.

The subaltern castes are represented very apparently through the celebration of Ambedkar as their caste icon in various scenes of the film, lyrics mentioning exterminated habitats and spatial differentiation of lower caste in the rural spaces of Tamil Nadu. The folk song “Engum Pugazh Thuvange” performed by Pariyan’s father; Puliyankulam Selvaraj is a direct representation of caste and identity through the folklore medium, where it actually portrays the life of Immanuel Sekaran, a dedicated leader and icon of the Pallar community (Dalits) in Tamil Nadu.

It subtly showcased the incidents of Ilavarasan’s honour killing in Dharmapuri, Keezhvenmani massacre, Manjolai Massacre, unethical media reportage of K R Narayanan’s demise, Kodiyankulam police riots, contentious worship in the cart festival of Kandadevi Temple, etc.

The director Mari Selvaraj has used popular songs from other Tamil films, composed by Maestro Ilayaraaja to carry out the soundscape of caste in the villages. The song used in the scene where the protagonist Pariyerum Perumal escapes from the higher-caste thugs, the song “Poradada! Por Valendhada”, a popular song from the movie Alai Osai (1985, Sirumughai Ravi) indicates the identity, spatial marker as well as the soundscape of the Dalits. This particular song has connotations of Dalit identity, specifically that of the Pallar caste. The dialogues like “Yeru pudicha kayyila naanum Vaazh pidichavanthan” (“My hands held the plough, but it also wielded swords”) brings a healthy discussion of equality and commemorates the clan history of the Dalits. The film also tried to represent the real-life incidents that happened in Tamil Nadu where the people of the Dalit community were exploited by the dominance of hegemonic caste groups as well as the authorities under the Dravidian party rule. It subtly showcased the incidents of Ilavarasan’s honour killing in Dharmapuri, Keezhvenmani massacre, Manjolai Massacre, unethical media reportage of K R Narayanan’s demise, Kodiyankulam police riots, contentious worship in the cart festival of Kandadevi Temple, etc.

It makes clear that the Thevar caste groups (intermediate caste) in Tamil Nadu, considers moustache as an indicator of social and caste power, embedded with their honour and pride.

Similarly, the higher caste; particularly dominant-intermediate caste are represented through celebration of Aruvals(sicke), and Silambam(martial sticks) as bodily codes representing the Thevar caste groups. Many scholars in the domain of sociology and cultural studies postulate that the celebration and usage of sickles are etched with the hegemonic Thevar caste as their imaginary martial heroism or martial supremacy of gore, valour, and suppression over submissive castes. ‘Sundaralingam’, belonging to the so-called intermediate caste, mentions his moustache with his caste pride during the clash with the protagonist. It makes clear that the Thevar caste groups (intermediate caste) in Tamil Nadu, considers moustache as an indicator of social and caste power, embedded with their honour and pride. This film also showcased the evil practice of disguising social reformers as caste leaders, where it emerges as caste violence for the disfiguring of the statues of Ambedkar and Muthuramalinga Thevar – two leaders deified as the caste iconography of power and tussles. It also depicted the reality of caste through coloured wrist bands used by the respective caste groups where the wristband of red and yellow represents Thevar caste and bands with green and red shows Dalits. It indicates caste identity, and discrimination.

Even though these elements can be analysed from the film, it never tried to make explicit caste and further forms of violence to the audience directly. The debutant filmmaker Mari Selvaraj seeks the society and asks people to rethink the extreme forms of impertinence existing in our society, which is embedded with casteist prejudices. This film is an intense portrayal of the caste-ridden society in which the dominant and hegemonic caste groups unleash acts of victimisation, exploitation, and humiliation at different levels against the vulnerable, gullible, and marginalised Dalits.

Very well written